Multinational retailers face new challenges to capture the increased spending power in each of these distinctive markets.

November 2007

In emerging markets around the world, the spending power of consumers is rapidly changing the retail industry, both globally and locally. Multinational retailers seeking new sources of growth are watching the mass markets of Brazil, China, and India, whose large populations and strong economic growth have made them nearly irresistible. As consumers have greater disposable income, they increasingly spend their money on items beyond the basic necessities. One of the first categories to feel this change is apparel.

To understand more fully what it would take for retailers to succeed in these markets, McKinsey conducted a proprietary research project on apparel-shopping attitudes and behavior in Brazil, China, and India. Our sample consisted solely of women,1 who in many markets not only decide what clothes to buy for themselves but also influence clothing purchases for their children and husbands. We supplemented this quantitative research with dozens of focus groups, store visits, interviews, and shopping diaries.

Our special report comprises articles on the retailing of mass-market apparel in China, India, and Brazil.

"India: Shopping with the family" explains the different roles that Indian women, men, and children play in making decisions about apparel and the way the market there is evolving.

Notes

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of their colleagues Susan Breuer, Claudio Lensing, Savita Pai, and Khiloni Westphely.

In memoriam: We dedicate this collection to the memory of Alastair Ramsay, a partner in McKinsey’s London office, who founded and led this research project. Alastair passed away in June 2007. He inspired us with his commitment to client service, as well as his warmth and compassion as a leader.

1 We surveyed 6,000 consumers of food, apparel, and electronics in Brazil, China, India, and Russia, including 900 women across Brazil, China, and India, specifically on apparel. In addition we surveyed 1,600 shoppers in France and the United States for the purposes of comparison.

China: Small budgets, small wardrobes

China’s clothing consumers are legion, but inexperienced about subcategories, quality, and features. Global retailers can help.

Wai-Chan Chan, Richard C. Cheung, and Anne Tse

Despite rapid growth, China’s apparel market presents global retailers with significant challenges. A McKinsey survey of Chinese consumers underscores the difficulty multinational retailers may face in applying to China their tried-and-true formulas for differentiating products and brands and suggests that they should adopt new approaches in areas such as in-store sales and advertising. Moreover, the survey highlights important differences between average Chinese apparel shoppers and the country’s young adults—a group that offers global retailers some intriguing possibilities.

These findings emerged from a research effort that combined a quantitative survey of urban mass-market consumers with qualitative research techniques, including shopper diaries, store visits, and focus groups.1 We studied the mass market because it increasingly drives the rapid growth (12 percent a year) of China’s $84 billion retail apparel market and represents a significant opportunity for foreign retailers to expand beyond the high-end consumers they have served since the early 1990s2 China’s apparel market is now the world’s third largest—behind only the United States ($232 billion) and Japan ($100 billion)—and the fastest-growing in the “BRIC” countries: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. Seventy percent of apparel sales in urban China take place in modern formats (typically, department stores, though more specialized shops have recently begun to emerge).

Our research indicates that China’s mass-market consumers have relatively small, undifferentiated wardrobes. Forty percent of the Chinese respondents, for example, report wearing similar clothing at work, formal social occasions (such as weddings), and dates with friends or family, compared with only 8, 13, and 11 percent of consumers in Brazil, India, and Russia, respectively. Although habits are changing, apparel retailers in China may find it more challenging than they do in other emerging markets to establish themselves as specialists in clothing subcategories, such as ladies’ office clothing or specialty outdoor casual clothing.

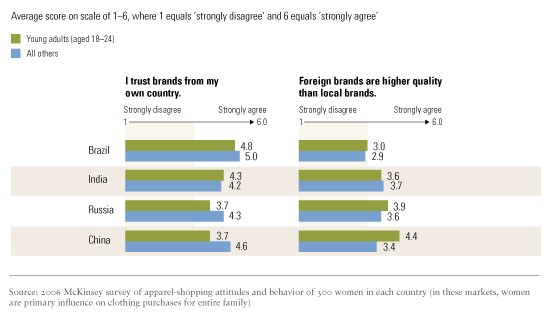

Moreover, Chinese consumers of apparel don’t appear to place a premium on foreign brands. Only one-quarter of the respondents say that such brands offer better value than local ones do, for instance, and only 11 percent report frequently trying on foreign offerings. These figures stand in stark contrast to our findings in India, where about 50 percent of respondents say that international brands are superior in value or quality. What’s more, Chinese shoppers seem to rely more heavily on price to form their perceptions of a product’s quality than do shoppers elsewhere. Whereas nearly half of the respondents in Brazil, India, and Russia believe that they can quickly assess the quality of a garment without taking its cost into account, only 22 percent of Chinese consumers say the same.

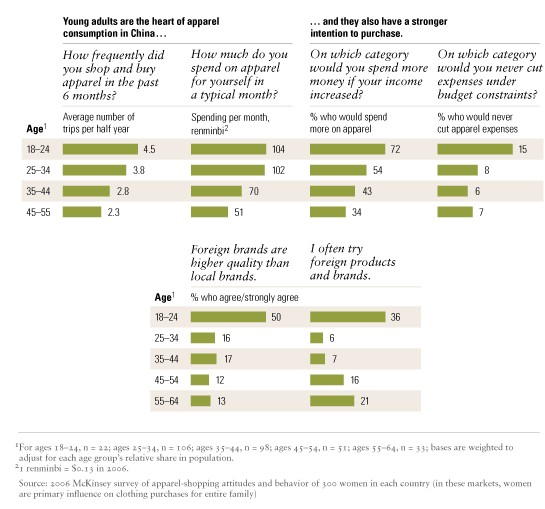

China’s urban young adults, from 18 to 25 years old—a segment comprising about 15 million people—represent an exception to these tendencies. Many young consumers favor international brands. Half agree that “foreign brands are higher quality than local brands,” compared with an average of 15 percent across all other age cohorts. Similarly, 36 percent of China’s young adults say they often try on foreign products and brands, compared with an average of only 13 percent of other respondents. Although young consumers behave differently from older ones in all of the countries we studied, the differences in China were by far the most pronounced (Exhibit 1). There young consumers also shop for apparel more frequently than do people in other age groups, spend larger sums on clothing, and are disposed to spend even more as their incomes rise (Exhibit 2).

These findings have several implications for global retailers. Clearly, targeting the young is a ripe opportunity and may require fewer changes to traditional merchandising and marketing approaches than serving older consumers would. To reach this brand-savvy segment, multinationals can create new, niche brands that convey specific personality traits—for example, irreverence or creativity. Retailers can also create lower-priced extensions of existing brands, as France’s Etam has with its “Etam Weekend” line.

Further, multinational retailers should help shoppers become better informed about clothing subcategories, product quality, and international brands. The recent strong growth of sportswear subcategories such as hiking and mountain-climbing lifestyle apparel suggests that the Chinese consumer’s desires are changing and could change faster if nudged. Companies that seek to shape the mass market’s evolution—say, through in-store sales efforts that highlight product features, seminars to help consumers discern product quality and craftsmanship, or advertising focused on the benefits of particular subcategories—should help improve customer satisfaction and loyalty. Esprit, based in Hong Kong, has successfully extended its brand into an increasingly diverse range of clothing lines (including casual, sporting, and work) by combining in-store elements (such as tailored display racks, lighting, and music) to communicate the essence of various subcategories.

As global retailers contemplate China’s mass market, they must recognize that they face more powerful local competitors there than in the higher end of the market. Indeed, the cost advantages of local players and their increasing ability to learn from global retailers’ store layouts and promotional campaigns will likely make it difficult to enter China’s mass market with a pure-value play. An alternative approach, which multinationals such as Zara are starting to use, involves identifying consumers willing to pay more for the latest fashions. By creating low-cost yet trendy stand-alone outlets in upscale malls or shopping districts (as opposed to department stores), retailers can appeal simultaneously to mass-market consumers with premium tastes and to higher-end customers prowling for bargains. Such strategies hold great promise as China’s mass market grows larger and richer.

About the Authors

Wai-Chan Chan and Richard Cheung are principals and Anne Tse is an associate principal in McKinsey’s Hong Kong office.

Notes

1We surveyed the apparel-shopping attitudes and behavior of 300 women, who in China (as in many other markets) not only decide what clothes to buy for themselves but also influence the clothing purchases of their children and husbands.

2For research purposes, we defined Chinese high-end (or global) consumers as those with annual household incomes greater than $12,200 (at 2005 exchange rates); mass-market consumers, incomes from $3,000 to $12,200; and struggling consumers, incomes below $3,000. The mass market can be further subdivided into a “consuming” group (with incomes from $5,000 to $12,200) and an “aspiring” one ($3,000 to $5,000).